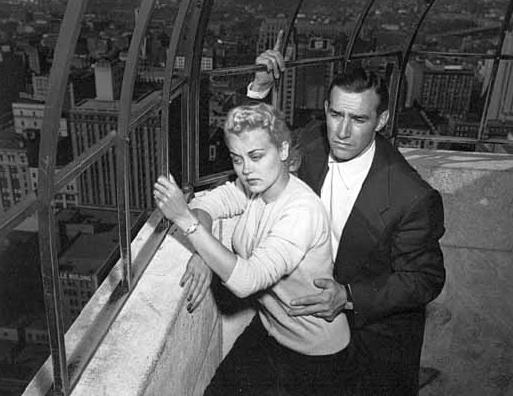

This little story was, I think, my first publication of the 21st century, appearing Eyeshot in 2004. Do you remember Eyeshot, webzines, and the Internet when it was weird and fun and hadn’t yet been enshitified? Yeah, me neither. Anyway, this story was inspired by stumbling across the photo above, from a photo shoot of actress and singer Laurie Anders on her 1951 visit to Minneapolis, atop the Foshay Tower. The dyspeptic looks on their faces caused me to dub them “The Unhappy Couple” and the bagatelle that follows flowed from their grimaces.

They had decided to jump with an air of sudden jocularity. All week they had commiserated over the hundred little tragedies that stained their lives: He complained that the Peterson account went to Bixby because Bixby had married a partner’s ugly daughter; she countered that the price of nylons at Schuneman’s had gone beyond the reach of her secretary salary; he told her that he suspected his wife was fooling around with the milkman; she had caught her fiancé in bed with a streetcar conductor named Bud; he had wasted his youth, and looked forward with dread to the long gray hours of middle age; she detested her youth and wished she had been born old.

On Thursday evening, working late at the firm, they made a pact and sealed it with a drop of blood from their left index fingers. At noon they went to lunch at Murray’s and told deeper sorrows yet over highballs filled with gin: Their childhood terrors at dark basements and fierce dogs, their constant headaches brought on by bright lights, their waking dreams during which they realized that if they were suddenly struck dead they would welcome the release. They stumbled out into the afternoon sun and the deserted downtown streets, giddy with gin and their mutual assignation. They sang “I Fall in Love Too Easily” in unison, boisterously and badly out of tune.

There was an ice cream shop on the ground floor of the Foshay Tower. She took his hand almost tenderly, certainly insistently, and said, “Just one last sundae, with butterscotch,” and he agreed, though he looked frequently at his watch while they shared a bowl with extra cherries.

Between the tenth and eleventh floors, while the elevator cables hummed and throbbed, he started to feel the churning in his gut. By the time they reached the thirty-first floor his existential pain had been replaced completely by the roiling in his stomach. He staggered out into the hallway and had to lean on her a little bit as they made their way up the stairs to the observation deck.

“Are you alright?” she asked.

He stood behind her and rested his hand against her flank. She felt fine and alive. Bile burned his throat.

“I’m fine,” he croaked. “It’s the ice cream.”

She rested her hand on one of the iron rods that framed the deck. It was solid and cold, but the spaces within the grid were ample and wide. Downtown stretched dirty and damp below them like a child’s discarded paper doll village in the rain.

“Are you sure you’re fine?” she asked.

He nodded and closed his eyes. The air felt cold and wet on his face, and he sucked it in deeply. He could smell her perfume — gardenias? hyacinth? He could never identify flowery smells.

“You don’t have to do this,” she said.

“Yes I do.”

She turned her face away from him; his breath was sour and hot, and he was standing too close. She wished she had come alone.

“Let me give you a boost,” he said to the back of her neck. She shrugged her shoulders at the rasping gargle in his voice. His chivalry disgusted her.

“No,” she said into the air over Marquette Avenue. Once again, she realized, she had chosen badly.