This is my biggest publishing coup to date: “The Oologist’s Cabinet” was picked up by Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, the journal/zine/weird tales publication put out by Gavin Grant and Kelly Link that has printed stories by Ted Chiang, Jeffrey Ford, Molly Gloss, and other incredible writers’-writers of the weird and fantastical. It was inspired by a wardrobe we once owned, and a news story about an allegedly extinct but possibly extant species of woodpecker.

My great-grandfather was an egg collector, one of the last of the gentleman oologists. At the height of his activities—he was born in 1886, and started raiding birds’ nests in about 1904—he had a reputation among collectors for daring and tenacity. In the newsletters and journals amateur oologists distributed among themselves, his initials—MQR, for Maxwell Quinn Russell—appear frequently above notes on the nesting habits of cliff-dwelling falcons and puffins, and sketches of rare tawny owl eggs. Other oologists, even some associated with universities in Chicago and Cleveland, corresponded frequently with him, asking him questions about the distribution of swallow-tailed kites and red-tail hawks, and the breeding patterns of spotted cuckoos. Toward the end of his life—he died in 1966, two years before I was born—he was gathering his papers for his memoirs, tentatively titled “The Egg-Collector’s Notebook.”

I know all this because I inherited his cabinet when my father died. It was a mahogany chest almost as tall as me, with intricate scenes of birds in flight and willow trees sighing beside winding rivers inlaid in teak and ivory. When the doors swung open and folded back against its sides, they revealed a warren of drawers and slots and yet more doors, many with yellowing index cards affixed to them behind gold-colored plates.

Inside the drawers and slots and cupboards were yet more boxes and small chests and papers tied with brittle blue and pink ribbons. And all of this nested containment, the boxes in boxes in boxes, was in the service of MQR’s collection of empty eggs. The cabinet was, in the end, a massive container of air.

My wife couldn’t stand the cabinet. Its vaguely Oriental styling and dark wood clashed with the bright, spare, modern furniture she prefers, and it gave off a camphor-and-dust odor when the doors were opened. Since it arrived at our house two years ago, a week after my father’s death, the cabinet squatted in almost every room, until finally it was banished to the back bedroom with everything else that is eventually forgotten: dresses and suits that have grown small as we’ve grown large, paintings that once seemed so avant garde but are now hopelessly dated, entire sets of dinnerware that are the wrong colors for the foods we eat now. The room was full to the point where it was almost impossible to walk through it, and the door stayed sensibly locked, as did my great-grandfather’s cabinet.

Locked, that is, until this week. Last month my wife told me to get rid of the cabinet, she didn’t care how: sell it, burn it, bury it at sea, just so long as it left the house. I couldn’t imagine dragging the cabinet, my great-grandfather’s life work, to the curb; I felt myself to be its curator, the keeper of a man’s passion, and I had to deliver it into the hands of someone who would continue in my stewardship.

So I made inquiries. The dealers in art objects and antiques whom we know would be not much interested in the cabinet; their world is full of Barcelona chairs and Corbusier lounges, brushed aluminum and stiff plastic. But they know people who know people who live in darker, mustier, rounder worlds, where shadows fill up corners and surprising specimens burst out of uneven drawers. I’ve seen shops, where apothecary tables are lined with jars of powdered monkey paws and extract of nightshade, and hat blocks split open to reveal lockets woven from corpses’ hair. We pass by those places, my wife and I, drawn instead to shiny surfaces like acquisitive crows, but I know they exist, so I know there is a race of people who surround themselves with camphor and dust.

I left my card with the dealers we know, with a brief description of the cabinet scribbled on the back: “oologist’s cabinet, c. 1912, Orientalist style with rare collection intact.” The dealers, thin men with wire-framed glasses and starched white collars, would look quizzically at the card, look at me and recall the International table or Mondrian sketch we had bought from them, and slip the cards into their pockets. And I would thank them, look longingly at the Bitossi bowls displayed in their windows, then go home and wait.

Then late one night, after my wife had gone to bed, the woman came to my door. It was raining out, had been raining for days, and her black coat faded into the darkness so that her pale face seemed to be floating in the dim porch light. She held up my card, on which the description of the chest was smudged as if she had worried it with her thumb, and looked up at me with a longing I have never seen before in a woman’s eyes.

I hurried her onto the porch and took her coat; she stood wordlessly, her lank black hair dripping onto her shoulders, until I put my hand gently in the small of her back and steered her inside. Even when we got to the locked door and I fumbled for the key she had not spoken; she looked straight ahead with those desperate eyes.

When I finally got the door open, I apologized for the clutter. But she was already halfway across the room before I had the light on, moving quickly and surely and never once stumbling against the boxes and crates, almost as if she were floating above the disarray. I followed as quickly as I could, banging my shins against the corners and making a meandering path through the clutter. When I joined her before the cabinet, she was tracing the delicate inlaid patterns with her bony fingers. She straightened herself, smoothed her simple black skirt, and looked at me again with parted lips and those beseeching eyes.

I fumbled on my chain again for the cabinet’s key, finally found it, and pulled open the doors. She stood in front of the warren of drawers and cupboards for several long moments, then knelt before the cabinet and pressed her palms against it. I thought I heard a low sigh, almost a moan, slide out of her mouth. I stepped back to give her space, almost tripping on a box full of old shoes.

She wasn’t pretty, barely handsome, with straight black hair to her shoulders and skin so pale it seemed blue. Her eyes were a little too big for her head, set far apart, and almost solid black; I couldn’t see the line between pupil and iris. She had thin, delicate hands with very long fingers, and elbows so sharp I thought they would cut open the sleeves of her white Oxford shirt. Her figure was like a child’s stick picture, with only the slightest curve at breast and hip. I couldn’t tell her age; she might have been anywhere between twenty and fifty. She gave off a smell something like gardenias floating in rainwater, sweet and loamy, with an undertone of decay.

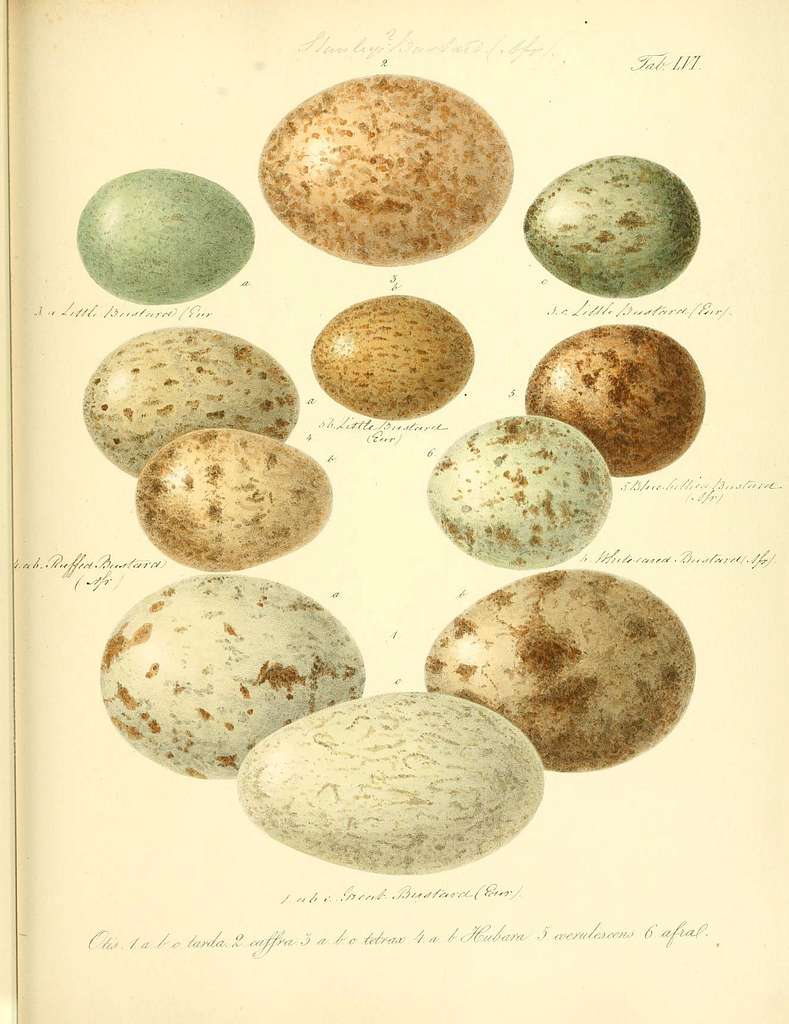

The woman ran her hand along the yellowed index cards on the lower drawers, then pulled one open: a wide, flat drawer containing the eggs of the common woodland mallard. She brushed her fingertips on the mottled brown shells resting on their bed of red felt, then gently lifted one out. When she held it up between her thumb and forefinger, the dim line shone through it. Oologists drilled tiny holes in the sides of their purloined eggs to drain out the yolks and let the delicate shells dry; sometimes they pressed their lips to the wound to suck the moisture away.

She pressed her own lips to the empty egg, and then rolled it along her pale cheek, closing her eyes. I held my breath, fearful that she would press too hard in her urgency and crack the fragile shell, but she rolled it so gently it was as if her hand never touched the surface of the egg. The she laid it back with its empty siblings and looked up at me with those black, imploring eyes. I knelt beside her, close enough to feel her warmth, and watched her slide the drawer shut.

When she pushed her mouth against mine, so hard I could feel her teeth behind her lips, I was too surprised to resist. She was dismayingly strong for something so slight, and so nimble and sure that I couldn’t have stopped her hands from pulling my belt clasp open if I had wanted to. And I didn’t want to, even for a moment, even with my wife sleeping upstairs and the carton of books pressing into my back when she pushed me onto the floor. She was incredibly light, as if her bones were hollow, and her touch was as delicate as goose down and as quick as hummingbird wings, and it was over as abruptly as it had started. By the time I sat up and realized what had happened she was gone.

I slept later than usual on the steel-and-leather couch in the living room, and was visited in my dreams by wheeling flocks of sparrows. When I woke up, my wife was in the kitchen making an omelet. The acid sting of fresh onions made my eyes water, and I pressed my nose into the clean smell of her yellow hair. But she pushed me away, complaining that I stank of musty old papers, so I left to shower, the memory of my strange visitor running in rivulets down the drain.

The memory came back during the day, though, and I found concentrating at work almost impossible. Everything reminded me of her: the sharp, light letter opener; the desk drawer full of pencils and paper clips; the long, delicate neck of my desk lamp. By the time I left for home I could see her pale hands pressed against my window and her black skirt fluttering on the coat rack. She had said nothing to me, but I knew more than hoped that she would return.

That night I waited until my wife went to bed, and I sat on the porch with MQR’s papers. I was reading about his 1913 journey down the Cache River in search of the ivory-billed woodpecker, when I heard the light tap against the window, almost inaudible above the raindrops. I found her waiting on the steps in her black coat with my smudged card again in her bony fingers.

I took her coat, folding it on my chair, and followed her to the back room, which I had left unlocked. We repeated the previous night’s scene, with slight variations. This time she went to the drawer full of pale blue robin’s eggs, and she wrapped one gently in her damp black hair before kissing it on the end and setting it back as if putting an infant to bed.

This time I was ready for her kiss, but she still overpowered me with her urgent shove. I tried to look up at her face, to hold her head in my palms, but she pinned my arms with her elbows and covered my eyes with her fingers, which were strangely webbed where they joined her hands. She let out a sigh and bit my lip before she stood. I watched her leave—I knew I wasn’t supposed to follow—and I tasted the metallic tang of blood on my tongue.

The next morning I managed to avoid my wife completely by rising early—I hardly slept at all, but I didn’t feel tired—and going in to work before anyone else arrived. I kept my office door locked but the windows open in spite of the rain. Had anyone looked in, they would have thought me hard at work. But I spent the day sketching eggs on the backs of envelopes: cream-colored hawks, black-striped terns, dainty white hummingbirds. I also tried to draw the woman but all I managed were her bony webbed fingers and round black eyes.

I came home early, before my wife, and went to the back room. In a cardboard box under the window I found some old clothes, and I took out a colorfully striped shirt that had been packed away years ago: orange on blue on green on red, alternating up the sleeves and down the front and back. Once it had seemed fashionable, but its tenure was short-lived. I put the shirt on, rolling the one I was wearing into a ball, and I was surprised to find it still fit, thought it was tight in the shoulders.

When my wife came home, she smirked at the shirt. I tried to tell her I thought I should bring some color back into my wardrobe, but she dismissed me with a wave of her hand and walked away. After she fixed herself supper and disappeared into her own room, I settled onto the couch again with MQR’s papers and waited, occasionally looking down to admire my shirt.

When she arrived at a little past midnight—I was dozing on the couch when she knocked—I tried to embrace her on the porch. I wanted to take her there, wordlessly and roughly, to prove that she wanted me and not my great-grandfather’s cabinet. But she pushed me away and went to the back bedroom, pausing at the hallway door to look over her shoulder at me and smile. She had never smiled at me before, and the expression was strange on her pale, blank face. I hurried after her.

That night was different from the previous two. She wore a simple brown slip instead of her black skirt and white Oxford, and when I caught up to her she turned to face me and pulled the slip over her head, revealing her pale nakedness. She was slender and boyish in build, narrow-hipped and hairless, though her belly was oddly distended. She waited for me to unlock the cabinet, then knelt and opened the cupboard containing the green heron eggs. While she held one of the hollow shells to her breast, I disrobed and took her from behind, at last in command of the scene. She held the egg gently no matter how roughly I applied myself, and she offered it to me over her shoulder. I kissed the egg, and her fingers, and the soft nape of her neck. Then she leaned forward, let out a cry that was sharp and shrill and only barely human, then pushed me away.

I fell onto my heels and watched her place the heron egg back into its cupboard. Her eyes were solid black disks when she bent down to kiss my forehead, and before I could speak she threw open the window and climbed out into the rain, leaving her dress behind.

In the morning a prepared a breakfast feast for my wife: thick slabs of toast smeared with strawberry jam, soft-boiled eggs, spicy Italian sausages fried until the edges were crisp black. She squinted at me and took just the toast. I ate the eggs and sausage and made more toast, but I was still hungry and stopped for donuts on my way to work.

At work that day I was unusually productive, putting the finishing touches on projects that had languished for weeks and getting a good start on work I had delayed for months. I found the previous day’s sketches and put them in my bottom drawer, face down. When I left in the evening, it was with a heart full of pride, and the feeling I had earned whatever pleasure might visit that night.

But when I came home, the door to the back bedroom was open and boxes filled the hallway. I hurried down the hall, but I knew what I would find. My wife was kneeling on the floor, in the spot where the oologist’s cabinet had stood, sorting shoes and dishes into cardboard boxes. She heard me stop at the door, and she looked up and smiled with a dramatic gesture at the empty space at the back of the room: “Gone.”

“Gone where?” I asked.

“Does it matter? Gone, gone for good.” The she reached into her pocket and took out a business card the color of old vellum. “A collector, in Germany. The movers carted it away this afternoon. And the rest of this—this junk—is going, too.”

I took the card, with its dense Teutonic lettering and strange phone number, and hoped it would reveal my lover’s name: Giselle, Jarvia, Marlena, Serilda. But it was a man’s name, Roderick, from the dark North Sea city of Hamburg.

The movers had not taken the bundle of papers I left on the porch, and that night I sat on the steel couch looking at MQR’s spindly script without reading the words. When she came again, would she smile over her shoulder as she doffed her dress, would she slip into the newly emptied room and evaporate like a ghost under halogen lamps? Would she still offer herself to me, the owner of a Bauhaus chair, without my magical box of air?

The rain was still falling—it seemed to have rained for years—and at first I thought the crash at the back of the house was a clap of thunder, though I’d seen no lightning. I listened for my wife’s footsteps on the stairs, but except for the staccato ping of rain there was silence. When I threw open the back room’s door, the window was open and rain spattered in droplets onto the clean wooden floor.

I almost left after I shut the window, but then I noticed, nestled between two boxes that hadn’t yet been cleared away, a round, mottled object. It was an egg, more spherical than oblong, cream-colored but speckled with black and brown. When I lifted it, the egg was heavy and warm and slightly damp to the touch, and it smelled of camphor and dust.

I pressed the heavy egg against my neck; I don’t know if I felt something pulsing inside it, or if I felt my own blood rumbling in my arteries. When I held it to my lips, I tasted blood and salt. The shell cracked easily against my tooth, and the yolk slid rich and golden down my chin.